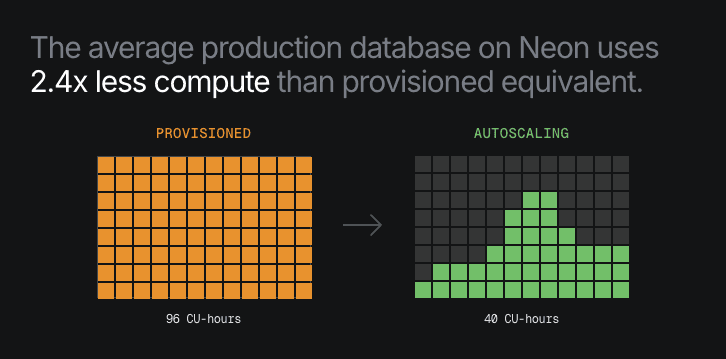

At Neon, we run hundreds of thousands of Postgres databases as ephemeral Kubernetes pods. Because of our scale-to-zero feature, every time a user connects to their database, there’s a chance that we need to spin up a new Postgres process to serve that connection.

The newly spun Postgres instance needs to be configured to serve that particular database for that specific user. In our architecture, the Postgres instance pulls this information from the Neon control plane. As we scaled the number of Postgres instances in our AWS EKS clusters, we observed that traffic to CoreDNS pods increased linearly with the number of active Postgres instances, as expected.

There were no signs of suboptimal DNS performance, and resource usage increased linearly with load.

Given that 95+% of the requests were cache hits at the CoreDNS pods, we saw an opportunity to take the overwhelming majority of DNS traffic off the network by distributing that DNS cache, trading some additional memory usage for lower DNS latency. This post is the story of how we deployed node-local-dns across our fleet, the benefits we reaped, and the lessons we learned along the way.

Node-local DNS in a nutshell

In popular managed Kubernetes setups (e.g., AWS EKS or Azure AKS), when a Pod performs a DNS lookup, the request is sent to the kube-dns Service ClusterIP and ultimately delivered to one of several CoreDNS pods running somewhere in the cluster.

This setup incurs a network round-trip to the CoreDNS pod (which directly causes extra latency), possibly contributing to network throttling (which causes errors that typically get retried at the application layer, ultimately surfacing as extra latency). Running a DNS cache locally to each node sidesteps both these issues, and that’s precisely what node-local-dns does.

We briefly discuss how to deploy node-local-dns for the sake of making this post self-contained, and refer the reader to resources available elsewhere (e.g., Kubernetes.io, Huawei, Tigera, T-Systems) for further reading.

Architecture

node-local-dns runs as a CoreDNS caching instance, deployed as a DaemonSet, on every node. This instance injects a virtual network interface onto the node and binds the IP address of the kube-dns service to it, therefore steering packets destined to the kube-dns service to that local interface and effectively making the local caching instance act as a transparent proxy. As a consequence, the Pods’ DNS configuration doesn’t have to change, allowing node-local-dns to be activated (and deactivated) live in a cluster.

The template also defines a separate kube-dns-upstream service that is entirely identical to kube-dns, except it has a separate IP address not bound to any local interface. This way, the caching instance still has a way to reach the CoreDNS pods.

Deployment

Several solutions exist for deploying node-local-dns, such as Helm charts. We chose to deploy the template from the official cluster add-on, using the substitutions recommended by the Kubernetes docs. Interestingly, the template upgrades the connection from the local DNS cache to the CoreDNS pods to use TCP (force_tcp). This nuance was instrumental to a lesson we learned in the process. We’ll come back to this aspect later.

We performed a gradual rollout across our production fleet after testing functional correctness and performance in a staging environment.

Performance gains

The results we observed matched—and in some cases exceeded—the trends reported by Azure AKS and Mercari.

Tail Latency

The most immediate impact was on the tail latency for DNS responses at the CoreDNS pods. Before node-local-dns, our 90pct DNS response time was around 220µs, 99pct was ~ 1.5ms (~8x the 90pct), and the 99.9pct was variable between 10ms and 20ms (on average, ~10x the 99pct).

After deployment, the 90th percentile remained roughly the same, the 99th percentile dropped to 240 µs (a ~84% improvement), and the 99.9th percentile dropped to <2ms (a ~87% improvement).

The cache hit rate at the central CoreDNS pod dropped to ~30%, indicating that the great majority of cache hits were now being served directly at the nodes, eliminating the network round-trip for frequent lookups.

Traffic load

As noted elsewhere, serving the majority of DNS requests in the node itself also reduces the load on the central CoreDNS pods. Our CoreDNS pods went from ~2k requests/s to ~60 requests/s, a 97% reduction.

Perhaps more important than the one-time reduction is the fact that the number of DNS requests that travel over the network now scales with the number of nodes, not with the number of Postgres instances.

Leaks and amplification mitigation

There’s one advantage that stems directly from the reduced load, and that we hadn’t anticipated initially. With the load down by more than one order of magnitude, it became much easier to inspect the DNS traffic at the level of individual requests, which revealed a surprising pattern of NXDOMAIN responses. We subsequently traced these back to leaking requests due to a misconfiguration in the /etc/hosts file. These ill-behaved requests tend to amplify as the resolving library reacts to NXDOMAIN responses by exploring the domains in the DNS search list one by one (see resolv.conf(5)).

Not only did node-local-dns allow us to identify the problem in the first place, it also provided a quick way to mitigate the misconfiguration: the version of CoreDNS in the node-local-dns image loads a few CoreDNS plugins, and in particular the template plugin, which allows crafting responses to specific requests directly in the configuration file. We used this mechanism to quickly blackhole the misbehaving requests directly at the node, without having to spend a round-trip on the network (not even on cache misses).

template IN A {

match "__THE_BAD_NAME__"

rcode NXDOMAIN

fallthrough

}Eventually, we also identified and fixed the misconfiguration in the offending images’ /etc/hosts file, but having a way to drop this traffic at the edge quickly was another benefit of node-local-dns that we hadn’t really expected.

Lessons Learned

It wasn’t a perfectly smooth sail. One failure mode we observed in our busiest clusters was the display of error messages, as shown below.

[ERROR] plugin/errors: 2 REDACTED.default.svc.cluster.local. AAAA: dial tcp 172.20.XXX.XXX:53: i/o timeout(172.20.XXX.XXX is the kube-dns-upstream service’s ClusterIP.)

It’s interesting to note that this error message is only logged because the force_tcp option in the configuration file forces the upstream connection to kube-dns-upstream to occur via TCP. (Over a UDP transport, it’s impossible to distinguish a query timeout from a connection timeout, since there’s no connection concept.) This error message, therefore, indicated a problem in communicating with the CoreDNS pods, rather than the CoreDNS pods’ inability to service requests.

We observed a spike in errors, similar to the one above, logged by a few nodes in our cluster. One particularly problematic node exhibited this pattern for several seconds before eventually self-healing.

The reason for the temporary unavailability of kube-dns-upstream is that there’s an inherent race between kube-proxy installing the iptables rules to make the ClusterIP reachable, and the node-local-dns Pod trying to forward requests to it. The node-local-dns manifest creates both the Service and the DaemonSet objects; however, nothing guarantees that kube-proxy will have installed the iptables rule for the Service before the Pod attempts to connect to it. In the overwhelmingly common scenarios, the race is quickly over, and nobody notices. On the problematic nodes, though, the time it took kube-proxy to install iptables rules was abnormally high. In turn, this was due to a difference in the default iptables backend.

Here’s the good news, though: you can avoid this race altogether by deploying the Service first and the DaemonSet later. If you experience high delays for kube-proxy syncs or want to play it extra safe, this might be the smoothest deployment option.

Interestingly, Cilium takes a different approach where steering the traffic is decoupled from deploying the DaemonSet. For this reason, Cilium users will want to deploy the components in reverse order: the DaemonSet first (without any access to the node networking stack), and then a Local Redirect Policy that redirects traffic destined to kube-dns on port 53 to the local DaemonSet’s listening address.

Conclusion

Deploying node-local-dns is one of the most straightforward actions you can take to improve latency in your cluster. It slashed our tail latency and helped us understand our DNS traffic patterns.

If you are running Kubernetes at scale, consider this. If using kube-proxy, keep its performance metrics in check as you gradually deploy node-local-dns.