Back when hashtags were a thing, you could search Twitter and find #NoStaging, a community dedicated to banishing the concept of staging from the development world. In the eyes of the #NoStagers, staging was costly, confusing, and corruptible.

And they were/are entirely correct.

A quick primer

The idea, of course, is that staging is an environment that mirrors production. It runs the same code, uses the same infrastructure, and works with data in the same way your live system does. You deploy to staging first, run tests, and verify everything works with production-like data and infrastructure. The goal of staging is simple – catch bugs and issues in a “real” environment before they reach your users.

The fundamental problem with staging: drift

The thing is, staging and production are two independent environments that are not naturally synchronized. They drift apart – not occasionally, not as an edge case, but continuously and inevitably.

Drift is the gap between what staging looks like and what production actually is, and it manifests in multiple forms:

- Data drift. Staging has yesterday’s data, manually edited test records, and reset sequences, while production has today’s transactions and untouched operational data

- Schema drift. Staging has last week’s table structure while production has this week’s indexes

- Transformation drift. Staging has anonymized fake data, while production has real patterns and relationships

Data drift: production keeps changing, staging is stale

Every traditional approach to staging involves managing drift, not eliminating it. The most common pattern is the simplest one: run a pg_dump against production, restore it into staging, run some ad-hoc scripts, and promise to refresh it again at a steady cadence.

No matter what though, your snapshot freezes a single moment in time, like a database version of Han Solo. Meanhile, production continues processing transactions. If the process of restoring takes hours to complete, staging already represents production as it existed hours ago.

But staging doesn’t just age, it also gets modified in ways production never does. An example is sequences. When you restore a dump, Postgres sets each sequence to the highest ID in the restored data. Production has 10,000 users, so users_id_seq gets set to 10000. What happens next?

- Tests start running in staging. Each new test user gets the next ID: 10001, 10002, 10003. Your test suite runs overnight and creates fifty test users with IDs 10001 through 10050.

- Production keeps running. Real customers sign up and get those same IDs: 10001, 10002, 10003.

- Now, staging user 10025 is a test account your QA team uses. Production user 10025 is a real customer who signed up last Tuesday.

Any code that references user ID 10025 means completely different things in the two environments. You can’t reproduce production issues in staging because the IDs point to entirely different records.

The traditional fix is automation: schedule the dumps with cron and run them nightly or weekly.This makes the drift predictable, but it doesn’t eliminate it – it institutionalizes the gap. Teams move to scheduled refresh cycles, hoping that regular updates will keep staging fresh enough. This works, but it’s of course not ideal:

- Staging is always stale by design. If you refresh nightly, staging is between 0 and 24 hours behind production. If you refresh weekly, that window extends to 168 hours. The schedule doesn’t eliminate drift; it just puts a ceiling on how bad it can get.

- Refresh windows collide with testing windows. The nightly refresh runs at 2 AM, takes three hours, and locks staging for writes. Developers in other time zones or CI pipelines hit a locked database. Tests fail not because of bugs but because of scheduling conflicts.

- Large databases make refreshes slow. As production grows, dump and restore times increase linearly. A database that took 30 minutes to refresh at 100GB takes hours at 1TB. The refresh window expands, collision risk rises, and staging becomes unavailable for longer periods.

- Partial refreshes introduce selective drift. To speed things up, teams copy only “core” tables and skip logging tables, analytics tables, or partitioned data. This works until a bug involves the interaction between a core table and a skipped table. The failure path doesn’t exist in staging because half the data isn’t there.

The next step is usually more automation – increase refresh frequency, add more pipelines, build incremental refresh systems that copy only changed data…. And then we hit the problems the #NoStagers foresaw: now you end up with a complex orchestration system built solely to keep staging “close enough” to production but never quite succeeding.

Schema drift: DDL changes never land the same way twice

Even if you could keep data perfectly synchronized, the database structure itself drifts independently. Migrations are supposed to be deterministic, but in practice, schemas diverge through several mechanisms:

- Hotfixes bypass the migration process. A critical bug requires an immediate ALTER TABLE in production. Someone promises to backport it to the migration system later and then forgets.

- Failed migrations get skipped. A migration fails in staging due to a data issue that doesn’t exist in production. The team marks it “skipped” and moves forward. The version number increments, but the schema change never happens.

- Extensions and configs drift independently. Production has certain Postgres extensions enabled, specific planner settings, or particular collation rules. Staging might have different versions, missing flags, or subtly different locale settings.

- Indexes drift over time. An index gets added to production to fix a slow query, but never propagates to staging. Or an index exists in staging for testing, but not in production.

This creates query plan divergence. A query runs against a small staging dataset, and the planner chooses a sequential scan. The same query in production, with millions of rows and different indexes, triggers an index scan. The query completes in 50ms in staging and times out after 30 seconds in production.

If you’re thinking, “use logical replication” – this solves data drift, not schema drift. Logical replication replicates DML (

INSERT,UPDATE,DELETE) but it doesn’t replicate DDL (ALTER TABLE,CREATE INDEX). If the schema diverges even slightly, replication slots break, or data replicates successfully but behaves differently due to missing constraints or indexes.

Transformation drift: more maintenance and abstraction

Once production contains PII, regulatory requirements prevent copying it unmodified into staging. Teams add a scrubbing layer that masks, randomizes, or removes sensitive data. This is drift by design – you deliberately transform the data to make it non-production-like, adding a new set of problems.

- Lossy transformations change application behavior. If your application depends on email uniqueness for user lookups, and your anonymization script replaces all emails with random addresses, you’ve broken that lookup. Geographic clustering becomes random distribution. Location-based logic produces different results.

- Referential integrity becomes fragile. Anonymizing parent keys without correctly updating child references breaks foreign key constraints. Hashed user IDs in one table but not in related tables breaks joins.

- Masking rules lag behind schema changes. A developer adds a new column with sensitive data. The schema migration deploys to both environments, but no one updates the anonymization script. That column leaks PII into staging unmasked.

- Non-deterministic randomization creates unpredictability. If your scrubber generates random fake data on each refresh, the same production record produces different staging values each time. Tests become flaky. Debugging becomes harder.

You can use a dedicated anonymization framework like Greenmask or pg_anon, which provides declarative rules for data masking. These tools help with the manual work and handle common edge cases, but they don’t eliminate the fundamental problem – you’re still maintaining a separate transformation layer that must stay synchronized with production schema changes, and as long as staging relies on a transformed copy of production, it will never truly match production behavior.

Drift is inevitable if staging is treated as a long-lived environment

All of these failure modes have a common root cause: staging is conceptualized as a cloned database instance, a long-lived copy of production that you create once, then try to keep “close enough” over time. The moment you do that, drift becomes inevitable.

A “cloned instance” is born stale. If you have a large database, it takes hours to be created, meanwhile production keeps changing while staging does not – and every hour that passes from there widens the gap. The best you can do is hope that when your tests run (hours or days later) the environment is still representative, but tests shoulnd’t care what production looked like last night but what production looks like right now.

If you could take an exact copy of production at the instant you need to test, almost every staging problem disappears. The challenge of course is that traditional databases make this impossible, unless your database is truly small – copying terabytes of data takes time.

But what if copying didn’t mean duplicating data? What if you could create a production-shaped database instantly, exactly when you need it, without creating a permanent clone? That’s the missing primitive, and that’s what we’ve built at Neon with branching.

Branches solve the drift problem

A database branch is a lightweight pointer to your production database at a specific point in time. It starts with the same schema and data as production, but uses copy-on-write storage: nothing is duplicated up front, and only the changes you make (the delta) are stored.

This changes how staging environments behave:

- No data drift, because branches are instant. Branch creation takes seconds because data isn’t copied. Thanks to copy-on-write storage, a branch references production’s current state at the exact moment it’s created. There’s no aging snapshot, no refresh cycle, and no long-lived clone slowly drifting out of date.

- No schema drift, because schema is inherited vs replayed. A branch starts with production’s exact schema without relying on migrations or DDL replays.

- No sequence divergence, because IDs aren’t reset. Since branches reference the same underlying data state, sequence values match production at creation time. You’re not restoring from a dump or reseeding IDs, so identifiers behave the same way they do in production.

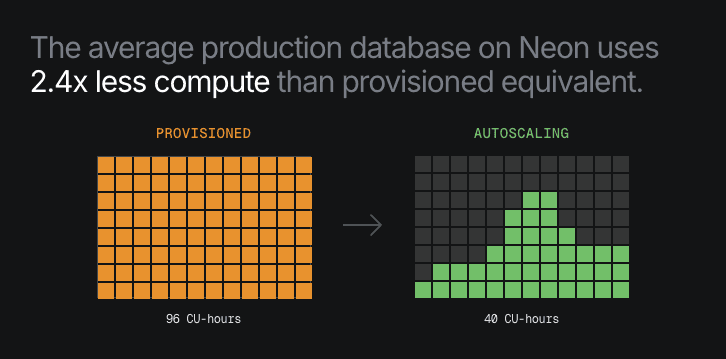

- No refresh windows, because branches are disposable. Instead of maintaining a single long-lived staging database, you create a fresh branch whenever you need one and delete it when you’re done. Compute is isolated per branch and scales to zero when idle, so there’s nothing to “refresh” or keep in sync.

- No transformation drift, because anonymization is built into branching. When production contains PII, you can create anonymized branches using declarative, per-column masking rules. Masking runs once at branch creation time and preserves schema, relationships, and data shape.

Instead of fighting drift in a long-lived staging clone, branching removes the conditions that cause drift in the first place.

When environments are temporary, drift disappears

Staging drift isn’t a failure of process or discipline but a structural problem with how databases get copied and maintained. The alternative is using branching workflows, which treat staging as ephemeral as any other environment. No drift accumulates because there’s nothing to maintain. Production stays production, everything else is temporary.

Try database branching on Neon, starting free.